|

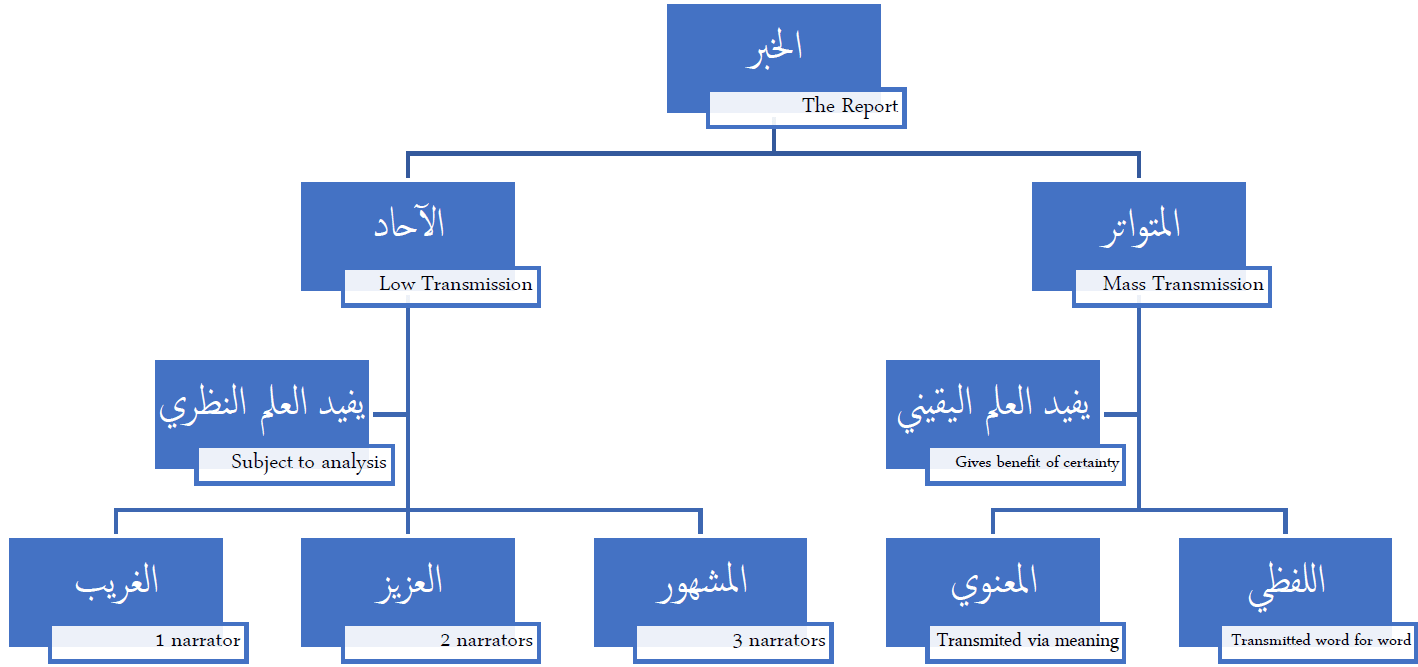

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم Khabar – Classification of ‘Aḥādīth I As discussed in the previous lesson, the term khabar refers to a report attributed either to the Prophet ﷺ, his Companions or both. In this section, we will explore the different categories of reports in terms of how many people have narrated them and the implication on the grading of such narrations, if any. Khabar can be divided in to two primary categories: 1. Khabar Mutawātir: A narration which has been narrated by a large number that cannot be quantified. 2. Khabar ‘Āḥād: A narration which has been narrated by a fixed number, a small number. Khabar Mutawātir – الخبر المتواتر Definition: Mutawātir is the active participle (اسم فاعل) of the word tawātur (تواتر). Linguistically it means for something to follow one after the other; succession, such as raindrops that follow in succession. Technically it means a report that has been narrated by so many people that it would be inconceivable to suggest that all these people could have come together and concocted such a lie. In light of this definition, a mutawātir narration is a ḥadīth or a khabar, which many narrators have reported in every single ṭabaqāh. A ṭabaqāh refers to one of the generations of narrators. In ḥadīth sciences, the first three generations are considered to be subject to analysis, as after these generations, ḥadīth at large had been preserved and transmitted on a mass level. These ṭabaqāt refer to the generation of the Companions, their successors (التابعين), and finally those who succeeded the تابعين known as the تبع التابعين. Otherwise referred to the three holy generations. Thus, the intellect dictates that, if so many narrators have reported the same narration in each one of these generations then it would be impossible to assume that all these narrators have agreed to fabricate this report. Conditions pertaining to khabar mutawātir: It is clear from the discussion surrounding the definition that a report will not be considered as mutawātir unless it fulfils the following four conditions: 1. Many people narrate it. There are various opinions as to what is the least number required for a report to be considered mutawātir. It seems that the preferable opinion is ten. 2. That these many narrators have reported it in each one of the three generations. 3. That it is impossible to assume all of them could have perpetuated such a lie. 4. That the report has been transmitted, narrator to narrator, generation to generation through ḥis (حس). Ḥis (حس)means that each narrator has transmitted to the next physically, that they have physically heard the report from their teacher and then physically transmitted that report to their own student in a similar fashion. Such as them saying; سمعنا (we have heard) or رأينا (we have seen). The ruling of mutawātir: The mutawātir report gives the benefit of ‘ilm yaqīnī (العلم اليقيني), otherwise known as ‘ilm ḍarūrī (العلم الضروري): i.e. it gives the benefit of certainty such that one is compelled to accept it as the truth and there is no room to deny it or reject it whatsoever. Thus, any report that is considered to be mutawātir must be accepted and acted upon. Types of mutawātir: A mutawātir report can be divided into two further categories: 1. Mutawātir Lafẓī – المتواتر اللفظي: Where the actual wordings of the report as well as the meaning is transmitted. a. For example: The narration, من كذب عليّ متعمدا فليتبوأ مقعده من النار – “Whom so ever attributes a lie to me intentionally, then let him set up residence in the Fire.” Over seventy Companions have narrated this report, and more in the following generations. 2. Mutawātir Ma’nawī – المتواتر المعنوي: Where the meaning has been mass transmitted, but the wording may differ in different reports. a. For example: The narrations regarding raising the hands during supplication. Approximately, a hundred narrations have been reported regarding it. However, all differ in wording. The individual reports cannot be considered to be mutawātir, nonetheless the action of raising the hands during supplication have indeed been reported as mutawātir. Availability of mutawātir: A good number of mutawātir narrations have been preserved including the following: · Narrations regarding the ḥawḍ (الحوض) · Narrations regarding wiping over the khuff (الخف) · Narrations regarding raising the hands in prayer However, in comparison to khabar ‘āḥād, the numbers are extremely low. Famous books regarding ‘akhabār mutawātirah: From amongst some of the books that have been compiled on this category, I have listed some below: · الأزهار المتناثرة في الأخبار المتواترة – By Suyūṭī · قطف الأزهار – Also by Suyūṭī · نظم المتناثر من الحديث المتواتر – By Muhammad bin Ja’far Kattānī Khabar ‘Āḥād – الخبر الآحاد Definition: Linguistically ‘āḥād is synonymous to wāḥid – the number one. Thus, a khabar wāḥid is what is narrated by one person. Technically, it is that report which does not fulfil the conditions of mutawātir. The ruling of ‘āḥād: The ‘āḥād report gives the benefit of ‘ilm naẓarī (العلم النظري): i.e. it has not yet reached certainty, but is subject to further investigation, after which it may indeed give the benefit of certain knowledge (العلم اليقيني). Khabar ‘Āḥād can be divided into three further categories: 1. Mash-hūr – المشهور – Three narrators in at least one generation 2. ‘Azīz – العزيز – Two narrators in at least one generation 3. Gharīb – الغريب – One narrator in at least one generation With the permission of Allah, we will discuss these categories further in the next lesson. Summary: Hope that was beneficial. May Allah the Exalted accept it from you and I both.

1 Comment

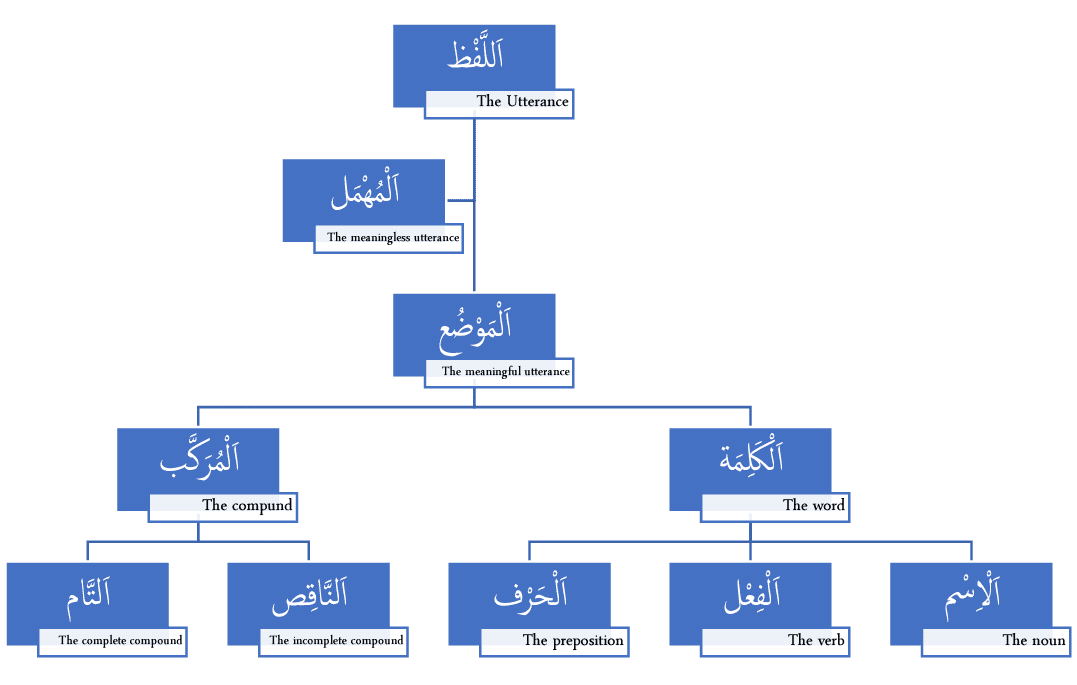

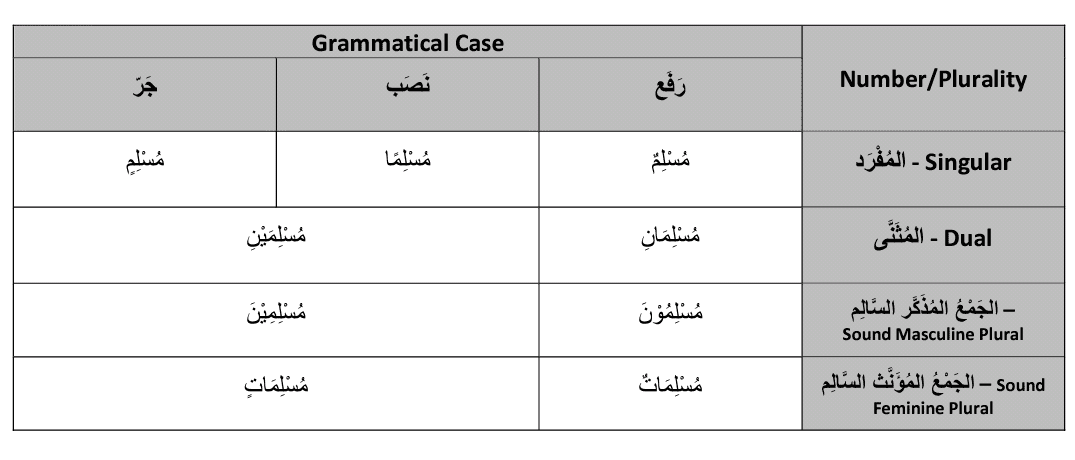

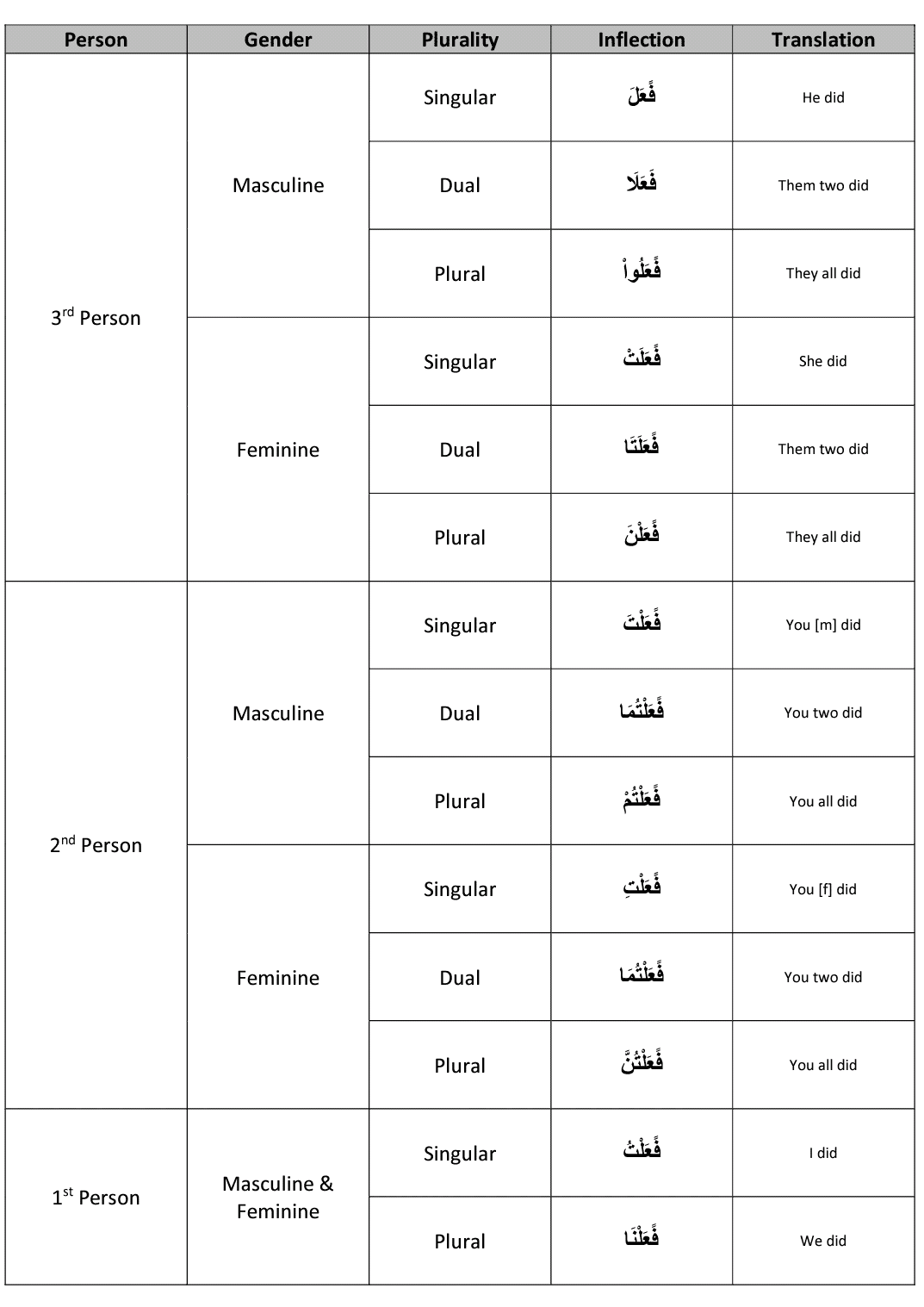

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم الحمد لله رب العالمين Recap of Lesson 1 – 7 In this lesson, we are going to recap some the rules that we have learnt in the last seven lessons: In the Arabic language, we have two types of utterances: 1. اَلْمَوْضُع – al-Mawḍū’ – that which has meaning 2. اَلْمُهْمَل – al-Muhmal – that which has no meaning An utterance is a form of linguistic communication that can be expressed verbally or in written form. All aspects of language that have meaning are called اَلْمَوْضُع (al-Mawḍū’). Whereas anything that is uttered and has no meaning, like gibberish, for example blah blah, is called اَلْمُهْمَل (al-Muhmal). So of course, we are going to be studying اَلْمَوْضُع. Meaningful language can be broken down into two sections: 1. اَلْكَلِمَات – words – which are the building blocks of language 2. اَلْمُرَكَّبَات – compounds – which are phrases or sentences formulated by putting words together. Letters alone don’t have any specific meaning. However, when you put letters together you can form a meaningful word. For example, ك and ت and ا and ب in and of themselves are just letters that don’t have any meaning. But put them together in a particular order, كِتَابٌ (a book), and you get a meaningful word that is coined to refer to something specific; in this case a book. There are three types of words in the Arabic language; Nouns, which are independent words the refer to names, places and objects; Verbs, which are action words that have a tense of past, present or future; Prepositions, which are dependent words that are usually linked to nouns and verbs. Now, you can put nouns and verbs together to formulate phrases and sentences. So far, we have studied one type of phrase, اَلْمُرَكَّبُ الْإِضَافِي (the genitive phrase); and one type of sentence, اَلْجُمْلَةُ الْاِسْمِيَّة (the nominal sentence). A phrase is an incomplete compound (اَلْمُرَكَّبُ النَّاقِص), which means that it is usually part of a sentence, i.e. it needs something else to be added to form a complete sentence; for example, رَبِّ الْعَالَمِيْن (the Lord of the worlds) is a genitive phrase that is incomplete but belongs to a larger sentence. A sentence on the other hand is a complete compound (اَلْمُرَكَّبُ التَّام), thus, it requires no extra words to complete it and can end with a full stop; for example, خَالِدٌ طَالِبٌ (Khalid is a student.) is a nominal sentence. This can be summarised in the following diagram: We also studied nouns in a little more depth: Definite and Indefinite Nouns Nouns can either be مَعْرِفَة (definite) or نَكِرَة (indefinite). A نَكِرَة noun is one which is devoid of any sign that indicates toward it being definite, such as كُرْسِيٌّ (a chair) or طَاوِلَةٌ (a table). A مَعْرِفَة noun is one which is, firstly, prefixed with the definite article ال, for example, اَلْكُرٍسِيُّ (the chair) and اّلطَّاوِلَةُ (the table). Note that when you add the definite ال to a noun, then the tanween at the end of the word drops. Secondly, a noun can be definite if it is a proper noun, such as a name of a person, for example خَالِدٌ or زَيْنَبُ. Thirdly, a noun can be definite if it is the first component of a genitive construct, i.e. the مُضَاف; for example, قَلَمُ زَيْدٍ (the pen of Zaid), here قَلَم is going to be definite even though it does not have an ال. Male and Female Nouns Nouns can be either masculine or feminine in the Arabic language. Usually, most nouns are masculine such as بَيْتٌ (a house) or مُعَلِّمٌ (a teacher). Also, any name belonging to the male genus will obviously be masculine, such as عَمْرو or مُحَمَّد. If a noun is suffixed with a ة (taa marbuta) then that word will be feminine, such as سَيَّارَةٌ (a car) or سَاعَةٌ (a clock). However, if the word is the name of a male person then it will be masculine regardless of the fact that it has a ة, such as حَمْزَة or طَلْحَة. Also, if a noun is a name belonging to the female genus, then obviously, it will be feminine, such as زَيْنَبُ or عَائِشَةُ. Lastly, some masculine nouns can be converted into female nouns if they refer to other female nouns, such as adjectives. This can be achieved by suffixing a masculine noun with a ة. For example, مُعَلِّمٌ means a male teacher, but add a ة, مُعَلِّمَةٌ then it means a female teacher. Grammatical Cases of Nouns Nouns can be rendered into different grammatical cases depending on what grammatical position they are placed into. If the grammatical case of a noun changes then the diacritic on the last letter of the noun will change accordingly. There are three grammatical cases for nouns in Arabic: 1. The رَفَع case: A noun that is in the رَفَع is called مَرْفُوع – and it usually ends with a dammah (ـُ) 2. The نَصَب case: A noun that is in the نَصَب case is called مَنْصُوب – and it usually ends with a fathah (ـَ) 3. The جَرّ case: A noun that is in the جَرّ case is called مَجْرُوْر – and it usually ends with a kasrah (ـِ) Singular, Dual and Plural Nouns A noun in Arabic can be either singular, dual or plural. The plurality of a noun can be changed by adding a different suffix to the end of a noun. The suffix will also depend on what grammatical case the word is in: ________________________________________________________________________________ We also studied phrases and sentences in a little more depth: The Genitive Phrase – اَلْمُرَكَّبُ الْإِضَافِي A genitive phrase is an incomplete compound which consists of two components: 1. The مُضَاف – The possessed 2. The مُضَاف إِلَيْه – The possessor For example, بَابُ الْمَسجِدِ (the door of the mosque). Here بَاب is the مُضَاف and المسجد is the مُضَاف إِلَيْه. The rules pertaining to each component is as follows: The مُضَاف: is usually definite and it will not accept a tanween nor the definite article ال. The مُضَاف إِلَيْه: is also definite and usually takes the definite article ال. And, it is always in the جَرّ case. The Nominal Sentence اَلْجُمْلَة الْاِسْمِيَّة The nominal sentence is a complete compound which also consists of two components. 1. The مُبْتَدَأ – the subject 2. The خَبَر – the predicate For example, اَلْمَدْرَسَةُ قَرِيْبٌ (the school is nearby). Here اَلْمَدْرَسَةُ is the مُبْتَدَأ, whilst قَرِيْبٌ is the خَبَر. The rules pertaining to each component is as follows: The مُبْتَدَأ: is usually the first noun of the nominal sentence, and is usually definite. Also, it is always in the رَفَع case. The خَبَر: usually follows the مُبْتَدَأ, and is usually indefinite. Also, it is always in the رَفَع case. The مُبْتَدَأ and the خَبَر will agree in gender and plurality. The Badal Compound The badal compound is a type of adjectival phrase (اَلْمُرَكَّب الْتَّوْصِيْفِي - we will study this in detail when it arises in the Qur’an). It also consists of two components. The unique aspect of this compound is that one component can be replaced by the other without changing the meaning. 1. The مُبْدَل مِنْهُ – the exchanged 2. The بَدَل – the exchanger For example, مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ عَبْدِ اللهِ (Muhammad son of ‘Abdullah). Here مُحَمَّدُ is the مُبْدَل مِنْهُ, whilst بْنُ عَبْدِ اللهِ is the بَدَل. In meaning, Muhammad is the son of ‘Abdullah, and the son of ‘Abdullah is Muhammad; thus, one could replace the other and we are still referring to the same person. The rules pertaining to each components are as follows: The بَدَل will always follow and emulate the مُبْدَل مِنْهُ in the following four aspects: 1. Being definite or indefinite 2. Gender 3. Plurality 4. Grammatical case _______________________________________________________________________________ We also studied verbs in a little more depth: Verbs Verbs in the Arabic language have three fundamental tenses: 1. اَلْمَضِي – Past tense 2. اَلْمُضَارِع – The present/future tense 3. الأَمَر – The command The base pattern of all the verbs is the past tense template. The following table will list the morphological inflections of the past tense verb in light of person, gender and plurality: Alhumdulliah, we have been able to extract all these rules from the first verse of Surah al-Fatihah.

With the permission of Allah, we will continue with the second verse in the next lesson. Hope this was beneficial. May Allah the Exalted reward you and I both. |

AuthorAbu Zuhair Archives

August 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed